|

|

|

Old Coley

Park

St. Mary's Reading

Coley Park was the home of the Vachell Family from at least 1287 until 1727. The family maxim,

Tis better to Suffer than to Revenge, is said to have come from an incident which took place here in the

late 14th century. John Vachell was in dispute with the

Abbot of Reading over rights of way through the former's estate. The Abbot sent a monk to test his rights with a load of corn. In a fit of rage, Vachell killed the poor man. He was excommunicated, heavily fined and given this unusual motto. In the early years of Vachell occupancy, Coley was a secondary estate, their main house being in

Tilehurst. Both medieval houses appear to have been substantial structures and we know that, in 1347, each had a private chapel erected within or adjoining them. By 1405, the family appear to have moved to Coley. Tilehurst became a lesser home for younger sons.

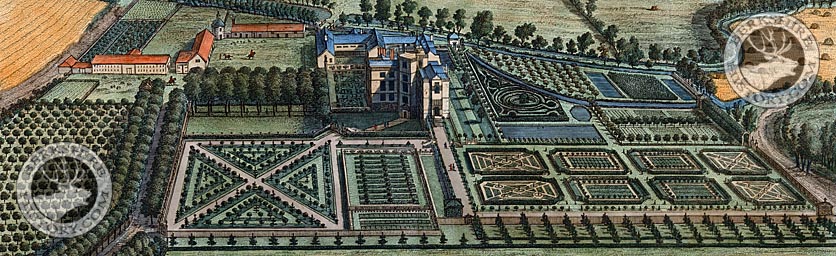

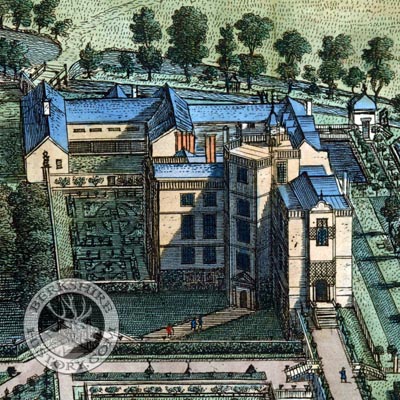

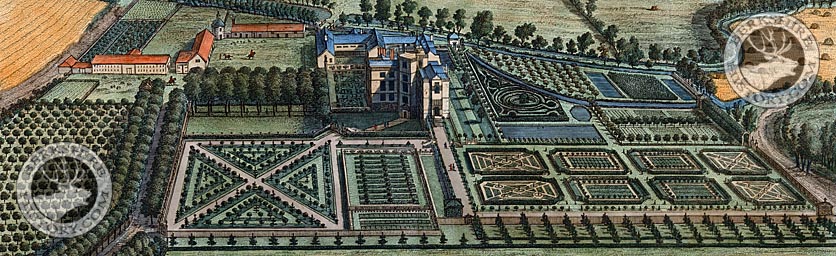

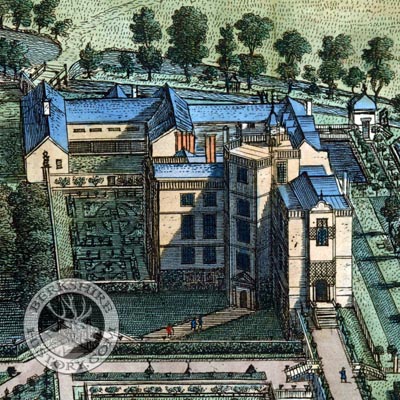

Old Coley Park is known from the above engraving dated about 1695. From this it would appear that, by the Tudor era, a new house had been built. Thomas Vachell, a close associate of Thomas Cromwell became very wealthy through his position as Supervisor of the Lands of the Dissolved

Reading Abbey. He may well have erected a fine Henrician mansion that reflected his new standing in the neighbourhood. A date

as late as 1555 has been suggested. Perhaps this survived at the core of the engraved house. The earliest parts we

see (close-up below), seem to be of slightly later Elizabethan date. The multangular turret, the balustrading and rendered finish are very reminiscent of Sir Walter Raleigh’s (New) Sherborne Castle in Dorset, erected in 1594. The turret’s position at the inner angle between two wings is another Elizabethan feature. Sometimes they were stair-turrets, sometimes porches as at Coley. It may have originally been topped by a bell-shaped roof, like that to be seen on the garden pavilion behind and to the right. This would line up with the lozenge datestone of 1593 TV on the surviving dovecote, seen to the left of the house in the engraving. However most of the house may be slightly earlier, Thomas Vachell Junior, as a recusant, had a third of his lands seized by the Crown in 1588. He went to live at his wife’s dowry property in Ipsden (Oxfordshire) and hid his treasury with his friends at

Ufton Court. He did not have Coley returned to him until 1603.

These strong features of the engraved house would, however, seem to represent only a portion of the original. For it seems rather an odd L-shaped structure with large low-level service quarters extending out the back. One would expect the wing projecting towards the artist to be one of a pair, with its twin at the other end of an extended version of the second wing, all three sides surrounding a courtyard. There may have been a second turret at the other inner angle; maybe even a more elaborate central porch. The projecting wing shows some evidence of possible Jacobean embellishment on the gable and stonework, perhaps undertaken by the recusant’s nephew, Sir Thomas Vachell, in 1619, the date of the surviving barns adjoining the dovecote. The engraving suggests such adjoining farm buildings, as part of the home farm, included stables, pig sties and chicken coops.

These strong features of the engraved house would, however, seem to represent only a portion of the original. For it seems rather an odd L-shaped structure with large low-level service quarters extending out the back. One would expect the wing projecting towards the artist to be one of a pair, with its twin at the other end of an extended version of the second wing, all three sides surrounding a courtyard. There may have been a second turret at the other inner angle; maybe even a more elaborate central porch. The projecting wing shows some evidence of possible Jacobean embellishment on the gable and stonework, perhaps undertaken by the recusant’s nephew, Sir Thomas Vachell, in 1619, the date of the surviving barns adjoining the dovecote. The engraving suggests such adjoining farm buildings, as part of the home farm, included stables, pig sties and chicken coops.

Sir Thomas, an apparent Royalist, died in 1638, four years before the outbreak of the Civil War. His heiress, Frances, had presumably predeceased him. She was the wife of William Deane, of Whitehouse in Havant (Hampshire). He was one of the Deanes of Old Basing, though his uncle came from

Swallowfield and his mother from

Streatley. Sir Thomas' heir was his nephew,

Tanfield Vachell, but he lived on the site of the

old Friary in Reading, whilst Lady Vachell continued to reside at Coley.

Lettice, Lady Vachell, was Sir Thomas’ third wife and the daughter of an old family friend,

Rear-Adm. Sir Francis Knollys, of

Abbey House in Reading (and Lord of the Manor of Battle Farm). Old Sir Francis, an ardent parliamentarian, outlived Sir Thomas by ten years. In 1640, Lady Vachell remarried to

Sir John Hampden and, no doubt, went to live at Hampden House in Great Hampden (Buckinghamshire). He was the man whose refusal to pay ship-money helped bring about the Civil War in 1642 and, unsurprisingly, he was killed at the Battle of Chalgrove Field the following year. Lady Hampden then returned to Coley. She is said to have watched the parliamentarians

besieging Reading from roof of the house. After this long siege, when the Parliamentarians had been victorious and the town’s defences destroyed, on 16th May 1644, Charles I spent the night at Coley House and his whole army camped in the park while marching from Oxford. Perhaps he was trying to

persuade Tanfield Vachell to remain a good Royalist, for he certainly abandoned their

cause not long aferwards. Lady Hampden may have been residing at her Dower House, ‘Lady Vachell’s House’ (later Finches Buildings) in

Hosier Street. The army later returned the way they had come via Englefield and

Compton. Symonds the

Diarist records the fine Vachell stained glass in the house at the time. Tanfield died in 1658 and there ensued legal wrangles over the disposal of his estates. The following year, Lady Hampden described the run-down state of the house at Coley, it having been “plundered in the time of the war between the late King and Parliament”. The disputes were only settled after her own death in 1666, when her will gives a few glimpses of

remaining splendour: ‘my suite of hangings of forest work which are in the dining room’ (referring to dense foliage-patterned tapestries), sixteen chairs all of needlework belonging to the dining room, the olive coloured bed, and the ten Knollys pictures belonging to her nephew. One can only imagine the latter were her family portraits saved from Abbey House when it was seized and sold off by Parliament.

Coley Park passed to Tanfield’s 2nd cousin, a lawyer, Thomas Vachell. He seems to have spent a quiet life there, taking part in parish business and attending

St. Mary’s Church in Reading. Perhaps this was because all his time was taken up with rebuilding and repairing the old house which, by this time, must have been in a considerable state of disrepair. A pillar in

the stables that probably came from the main house was dated T&AV 1679. It was probably Thomas who found it necessary to pull down the western wing of the building and, indeed, part of the main body. Having consolidated what was

left and added some modern touches, like the cupola on the roof, he laid out the surrounding gardens in the latest Dutch Baroque style with avenues of trees, rectangular parterres made of rigid formal hedges, a maze, topiary, arch-covered walkways, canals and other ornamental water features fed by the Holy Brook. Note also, from the engraving, how the garden is terraced on a number of levels. The approach to the projecting wing is higher than the garden on both sides, and higher still than the entrance front to the house. The wing door enters at the second, if not the third, storey.

Coley Park passed to Tanfield’s 2nd cousin, a lawyer, Thomas Vachell. He seems to have spent a quiet life there, taking part in parish business and attending

St. Mary’s Church in Reading. Perhaps this was because all his time was taken up with rebuilding and repairing the old house which, by this time, must have been in a considerable state of disrepair. A pillar in

the stables that probably came from the main house was dated T&AV 1679. It was probably Thomas who found it necessary to pull down the western wing of the building and, indeed, part of the main body. Having consolidated what was

left and added some modern touches, like the cupola on the roof, he laid out the surrounding gardens in the latest Dutch Baroque style with avenues of trees, rectangular parterres made of rigid formal hedges, a maze, topiary, arch-covered walkways, canals and other ornamental water features fed by the Holy Brook. Note also, from the engraving, how the garden is terraced on a number of levels. The approach to the projecting wing is higher than the garden on both sides, and higher still than the entrance front to the house. The wing door enters at the second, if not the third, storey.

Such major building work must have cost Thomas dearly, for, by the time he wrote his will in 1683, he was seriously in debt. He asked that all his personal belongings

be sold, including the “pictures and curiosities designed by [his] late cousin, Tanfield,”

to correct his state of insolvency. Unfortunately, however, this was not enough and his son, Tanfield II, with a large family to support, continued in debt until he was forced to mortgage the estate. The engraving was made during his occupancy. He died in 1705.

As early as 1717, Tanfield’s widow, Dorothy Vachell, and her young son, Thomas, seem to have rented out Coley to Lieut-Col Richard Thompson. Thompson was a rich sugar plantation and slave owner from Jamaica, who had been a member of the Jamaican Assembly and Council. However, in 1711, he decided to settle in England. His father, William, had been a younger son of Sir Samuel Thompson, nephew of Lord Haversham and sometime Lord Mayor of London, who had long resided at

Bradfield Place (and

previously at Osterley Park), so Richard must have known the area well. Thomas Vachell died in 1719 and was succeeded in the ownership of Coley by his brother, William. When their mother followed the former to the grave in 1726, William was probably already in marriage negotiations with the family of the late Edward Chester of Cokenach at Barkway in Hertfordshire for the hand of his daughter & heiress. The following year, he sold Coley to Thompson. In 1729, he married Catherine Chester and the two set up home at Abington Lodge at Great Abington in Cambridgeshire.

It was probably Col. Thompson who remodelled the southern river-facing side of the old Jacobethan house at Coley with a centrally pedimented Palladian facade popular at that

time (see monochrome engraving above). He died in 1735, but his will was not proved for some four years, probably indicating that his son, Richard Nicholl Thompson, had died within this intervening period, as he is not heard of again. So Thompson’s three daughter, Jane, Anne and Frances, inherited the property jointly. The two spinster daughters lived on there for another sixty years, but Anne married Sir Philip Jennings (later Jennings-Clerke) bart and the couple lived mostly at their home in the New Forest, Foxleaze at Lyndhurst, although they owned several other properties. The Thames Valley home of Jennings’ father had been the Priory at

Beech Hill and he had many relatives amongst the local Berkshire gentry. Sir Philip and his son both died in 1788 and Anne’s sisters were gone by 1791. She and her surviving child, Frances, sold Coley the following year to William Chamberlayne, Solicitor to the Treasury. Three years after his death in 1799, his son of the same name sold Coley after having inherited Cranbury Park in Hampshire. It was briefly owned by Thomas Bradford of Woodlands near Doncaster before being purchased by John McConnell. Soon afterwards, due to flooding problems, he pulled down the house near the Holy Brook, leaving only the farm, and had architect, Daniel Asher Alexander, use the materials to erect for him a new structure on the hill above. This was sold to the Monck family in 1810 and still stands in use today as a private hospital.

|

|

These strong features of the engraved house would, however, seem to represent only a portion of the original. For it seems rather an odd L-shaped structure with large low-level service quarters extending out the back. One would expect the wing projecting towards the artist to be one of a pair, with its twin at the other end of an extended version of the second wing, all three sides surrounding a courtyard. There may have been a second turret at the other inner angle; maybe even a more elaborate central porch. The projecting wing shows some evidence of possible Jacobean embellishment on the gable and stonework, perhaps undertaken by the recusant’s nephew, Sir Thomas Vachell, in 1619, the date of the surviving barns adjoining the dovecote. The engraving suggests such adjoining farm buildings, as part of the home farm, included stables, pig sties and chicken coops.

These strong features of the engraved house would, however, seem to represent only a portion of the original. For it seems rather an odd L-shaped structure with large low-level service quarters extending out the back. One would expect the wing projecting towards the artist to be one of a pair, with its twin at the other end of an extended version of the second wing, all three sides surrounding a courtyard. There may have been a second turret at the other inner angle; maybe even a more elaborate central porch. The projecting wing shows some evidence of possible Jacobean embellishment on the gable and stonework, perhaps undertaken by the recusant’s nephew, Sir Thomas Vachell, in 1619, the date of the surviving barns adjoining the dovecote. The engraving suggests such adjoining farm buildings, as part of the home farm, included stables, pig sties and chicken coops. Coley Park passed to Tanfield’s 2nd cousin, a lawyer, Thomas Vachell. He seems to have spent a quiet life there, taking part in parish business and attending

Coley Park passed to Tanfield’s 2nd cousin, a lawyer, Thomas Vachell. He seems to have spent a quiet life there, taking part in parish business and attending